Why Communication Metadata Matters

Last Reviewed: July 22, 2024

As its name suggests, metadata is data about data. Metadata is used in a variety of contexts, often for cataloging information, like tagging keywords in a video so it’s easy to find later. When it comes to computers, people often first think of "file metadata," which includes details about when a file was created, by who, the type of file, and more. You have likely encountered this type of metadata at some point on your computer when trying to figure out when you created a file, or even on your phone when looking at information about a photo you took, such as metadata on innocuous information like the aperture and shutter speed used in the photo, or information like the location the photograph was taken.

If you want to take a closer look at how file metadata works, Freedom of the Press Foundation dives into a couple specific examples.

When it comes to communications, metadata can be particularly revealing, potentially allowing a third-party—like law enforcement or another government entity—to infer details about the contents of that communication even though they do not have access to that. This is the type of metadata we'll be talking about in this guide.

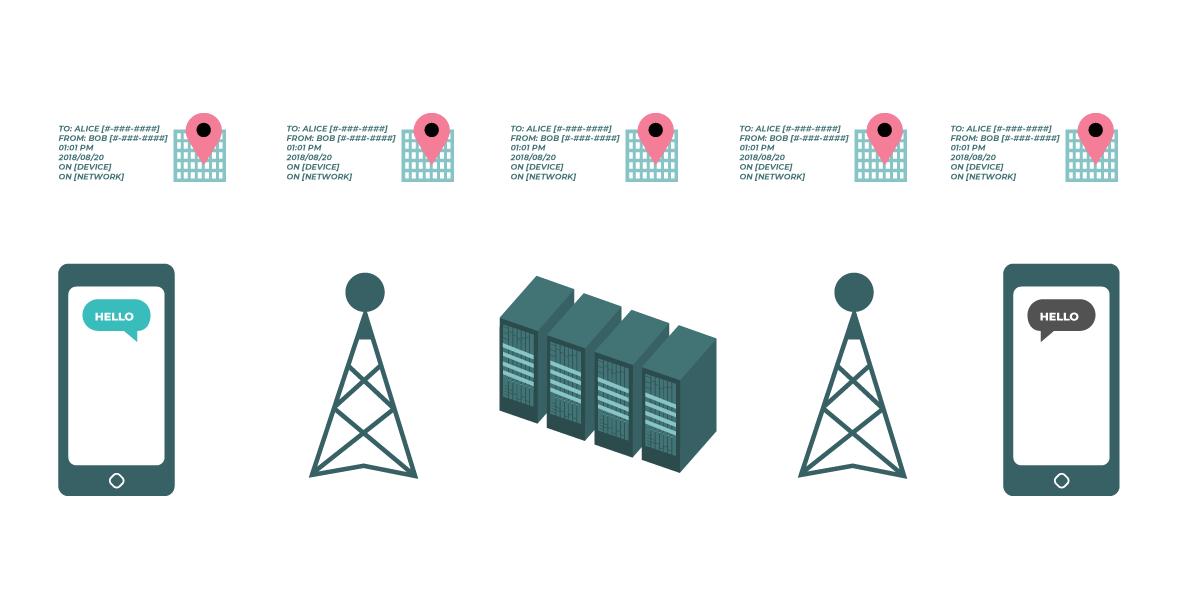

Communication metadata is essentially everything except the content of your communications. You can think of metadata as the digital equivalent of an envelope. Just like an envelope contains information about the sender, receiver, and destination of a message, so does metadata. Metadata is information about the digital communications you send and receive. Some examples of metadata include:

- The subject line of your emails

- The length of your conversations

- The time frame in which a conversation took place

- Your location when communicating (as well as with whom)

Historically, metadata has had less privacy protection under the law in some countries—including the U.S.—than the contents of communications. The police in many countries can obtain the records of who you called last month more easily than they can arrange a wiretap of your phone line to hear what you’re actually saying. Or, a government agency could purchase metadata without needing to clear the sorts of technical or legal hurdles that might be required to read content.

Those who collect or demand access to metadata, such as governments or telecommunications companies, argue that the disclosure (and collection) of metadata is no big deal. Unfortunately, these claims are just not true. Even a tiny sample of metadata can provide an intimate lens into a person’s life. Let’s take a look at how revealing metadata can actually be to the governments and companies that collect it. A telecommunications company may know:

- You called the suicide prevention hotline from the Golden Gate Bridge.

- You got an email from an HIV testing service, then called your doctor, then visited an HIV support group website in the same hour.

- You received an email from a digital rights activist group with the subject line “Tell Congress: KOSA Will Censor the Internet But Won't Help Kids” and then called your elected representative immediately after.

- You called a gynecologist, spoke for a half hour, and then called the local abortion clinic’s number later that day.

It can be difficult to protect your metadata from external collection because third parties often need metadata to successfully connect your communications. Just like a postal worker needs to be able to read the outside of an envelope in order to deliver your message, digital communications often need to be marked with source and destination. Mobile phone companies need to know roughly where your telephone is in order to route calls to it. Some software, like Tor and Signal, try to minimize the amount of metadata they collect, but this is still rare with most software. When it comes to your web browsing, some privacy enhancements may be possible with protocols like Encrypted Client Hello, which can hide which websites you visit from an ISP or other eavesdroppers.

Until laws are updated to better deal with metadata, and the tools that minimize it become more widespread, the best thing you can do is to be aware of what metadata you transmit when you communicate, who can access that information, and how it might be used.