位置追踪

最后更新: November 05, 2024

手机最严重的隐私威胁(却经常被完全忽视)在于,通过发出的信号来暴露用户的行踪。一台手机的位置至少可通过四种方式被他人追踪:

- 基站的移动信号追踪

- 蜂窝基站模拟器的移动信号追踪

- Wi-Fi 与蓝牙追踪

- 应用及网页浏览导致的位置信息泄露

移动信号追踪——基站

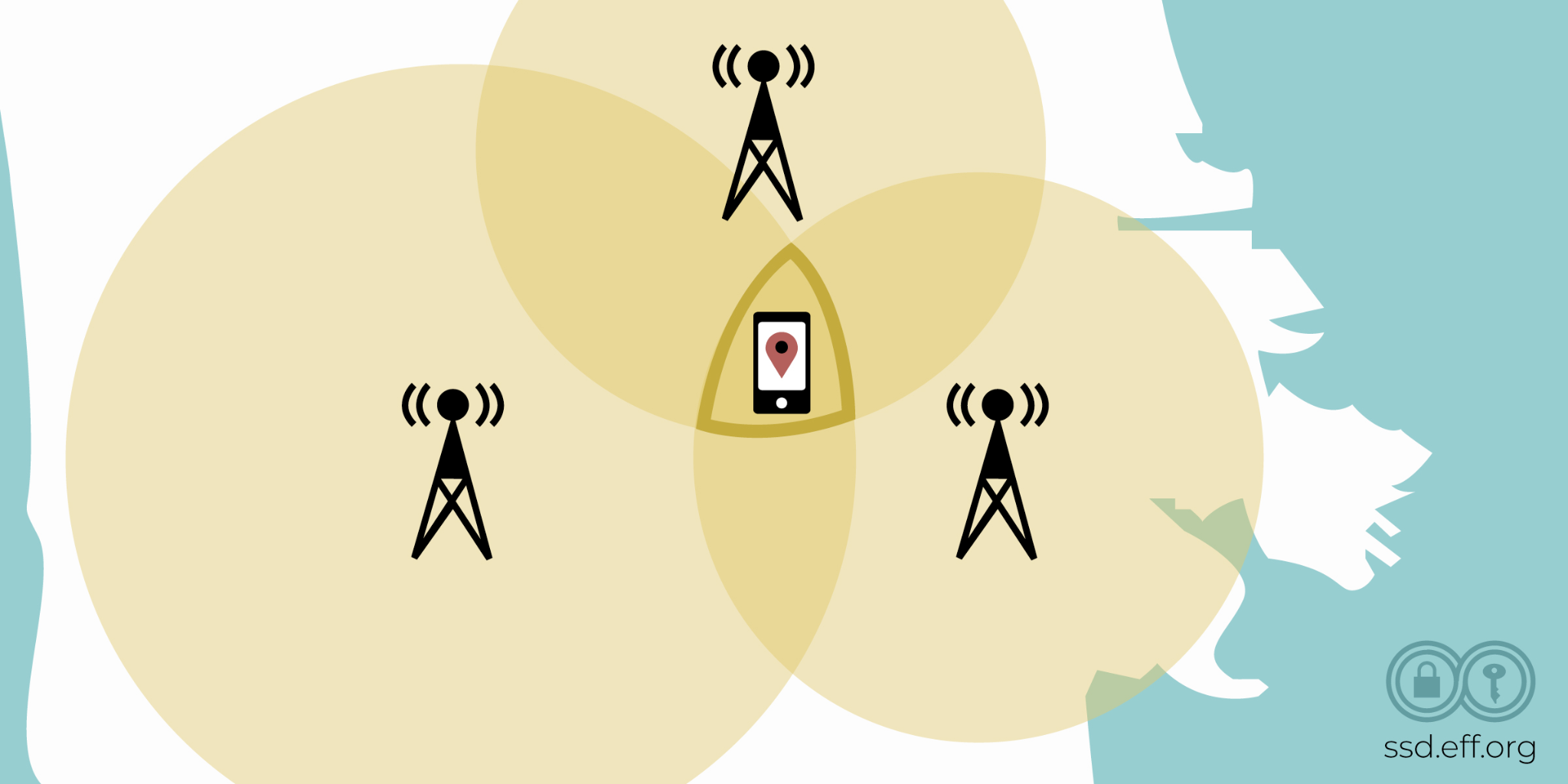

在所有现代移动网络中,只要手机处于开机且接入网络的状态,蜂窝网络服务商即可计算出特定用户的手机位置。此能力源于蜂窝网络基站的部署方式,通常称为“三角定位法”。如果您看过现代犯罪题材的影视剧,想必对该术语不陌生。

![]()

移动运营商实施三角定位的一种方法是:观测不同基站对某用户手机信号的接收强度,进而推算出设备位置。此过程通过“信号到达角”测量来完成。

此类定位测量的精确度受多种因素的影响,包括运营商采用的技术及区域内基站的密度。通常,在至少三个基站的覆盖下,运营商可将定位范围缩小至 3/4 英里(约 1 公里)。对于支持“locationInfo-r10”功能的现代手机及网络,运营商还会使用三边测量法。该功能生成的报告中包含手机精确的 GPS 坐标,其准确性远超三角定位法。

只要用户的手机处于开机状态、插入有效的 SIM 卡并向运营商网络发送信号,便无法规避此类追踪。

尽管通常只有运营商能执行此类追踪,但政府可强制其提交用户位置数据(实时或历史记录)。2010 年,德国隐私倡导者 Malte Spitz 依据隐私法,要求运营商交出其个人位置记录,并将该记录作为教育资料公开发布,以帮助公众理解运营商如何以此方式监控客户。政府获取此类数据的可能性并非理论假设:各国执法机构已广泛使用,包括美国。2018 年,美国最高法院在卡朋特诉美国案中裁定:根据第四修正案,警方必须获得搜查令方可从运营商处获取此类历史位置数据(称为“基站位置信息”,简称 CSLI)。判决书指出,历史 CSLI 会形成“对一个人多年来每天、每时每刻行踪的详尽记录”。

另一类政府数据请求称为“基站数据批量调取”,即,要求运营商提供特定时段内出现在某区域的所有移动设备的清单。此手段可用于刑事侦查,也可用于识别特定抗议活动的参与者。EFF 已诉请法院判定基站数据批量调取违宪,因其违背第四修正案对“搜查范围过度宽泛且缺乏合理依据”的禁止条款。

运营商之间也会共享设备位置数据。此类数据的精确度低于多基站协同追踪的结果,但仍可作为个体设备追踪服务的基础——包括通过商业服务查询此类记录以定位某部手机当前在何处接入移动网络。这种追踪不涉及强制运营商提交用户数据,而是利用商业渠道可获得的位置数据。

应对措施:由于此过程由运营商控制,除了不随身携带手机,用户几乎无法加以阻止。若运营商告知您,执法机构已通过法庭命令或搜查令要求获取您的数据,您可以联系 EFF 法律援助部门,咨询应对方案。

移动信号追踪——蜂窝基站模拟器

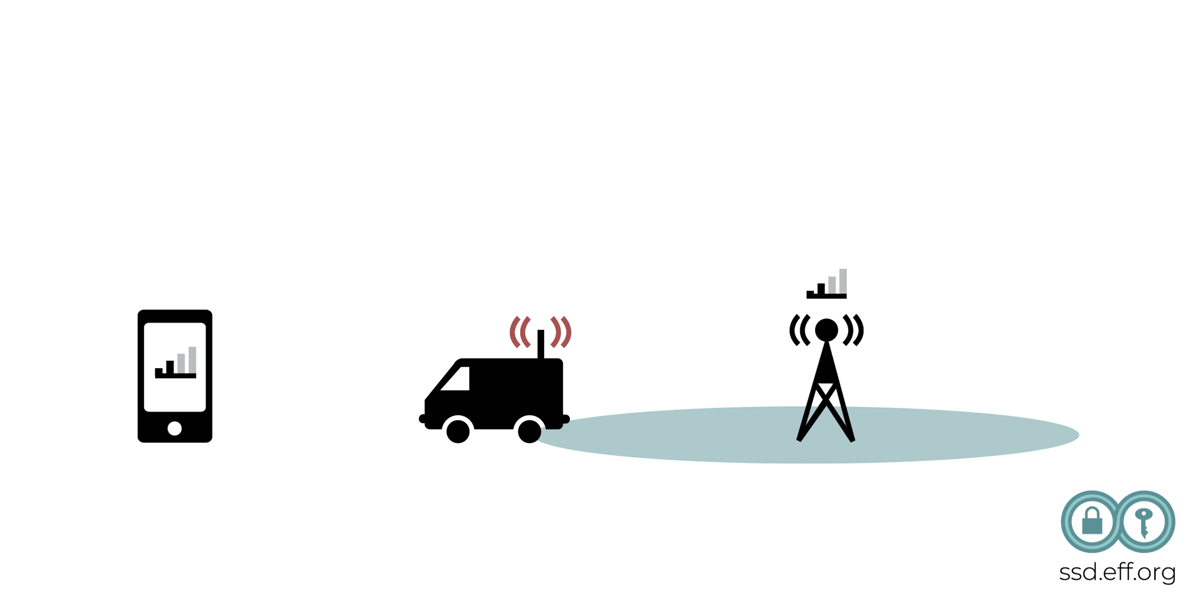

政府或技术先进的组织也可直接采集位置数据,例如使用蜂窝基站模拟器(又称 IMSI 捕捉器或“黄貂鱼”)。这类便携式伪基站伪装成真实基站,旨在“捕捉”特定用户的手机信号,检测其物理位置并监控其通信内容。IMSI 是指国际移动用户识别码(用于识别特定用户的 SIM 卡),但 IMSI 捕捉器也可能通过设备的其他特征来锁定目标。

![]()

IMSI 捕捉器需部署至特定区域方能对该区域的设备进行定位或监控。执法机构需取得搜查令方可使用 IMSI 信号拦截技术(多数情况下,还需额外获得通讯记录令等法律授权)。但“非官方”伪基站(非执法机构设立)则完全脱离法律约束运行。

应对措施:目前有若干种防御 IMSI 捕捉器的手段。在安卓设备上,可以禁用 2G 连接(多数 IMSI 捕捉器依赖 2G 协议)。iPhone 用户可通过启用“锁定模式”来关闭 2G 功能,但此举将同时停用多项其他功能。此外,建议使用 Signal、WhatsApp 或 iMessage 等加密通信工具,确保通信内容无法被截获。

Wi-Fi 与蓝牙追踪

现代智能手机除移动网络接口外,还配备其他无线电发射器,以及 Wi-Fi 和蓝牙功能。此类信号的发射功率低于移动信号,通常仅在短距离内可接收(如同一房间或建筑内),但使用高灵敏度天线的攻击者可能可以从超远距离探测到这些信号。例如,2007 年,委内瑞拉一位专家在无线电干扰较低的农村环境下,于 382 公里(约 237 英里)外接收到了 Wi-Fi 信号。不过,此类极端场景极为罕见。

![]()

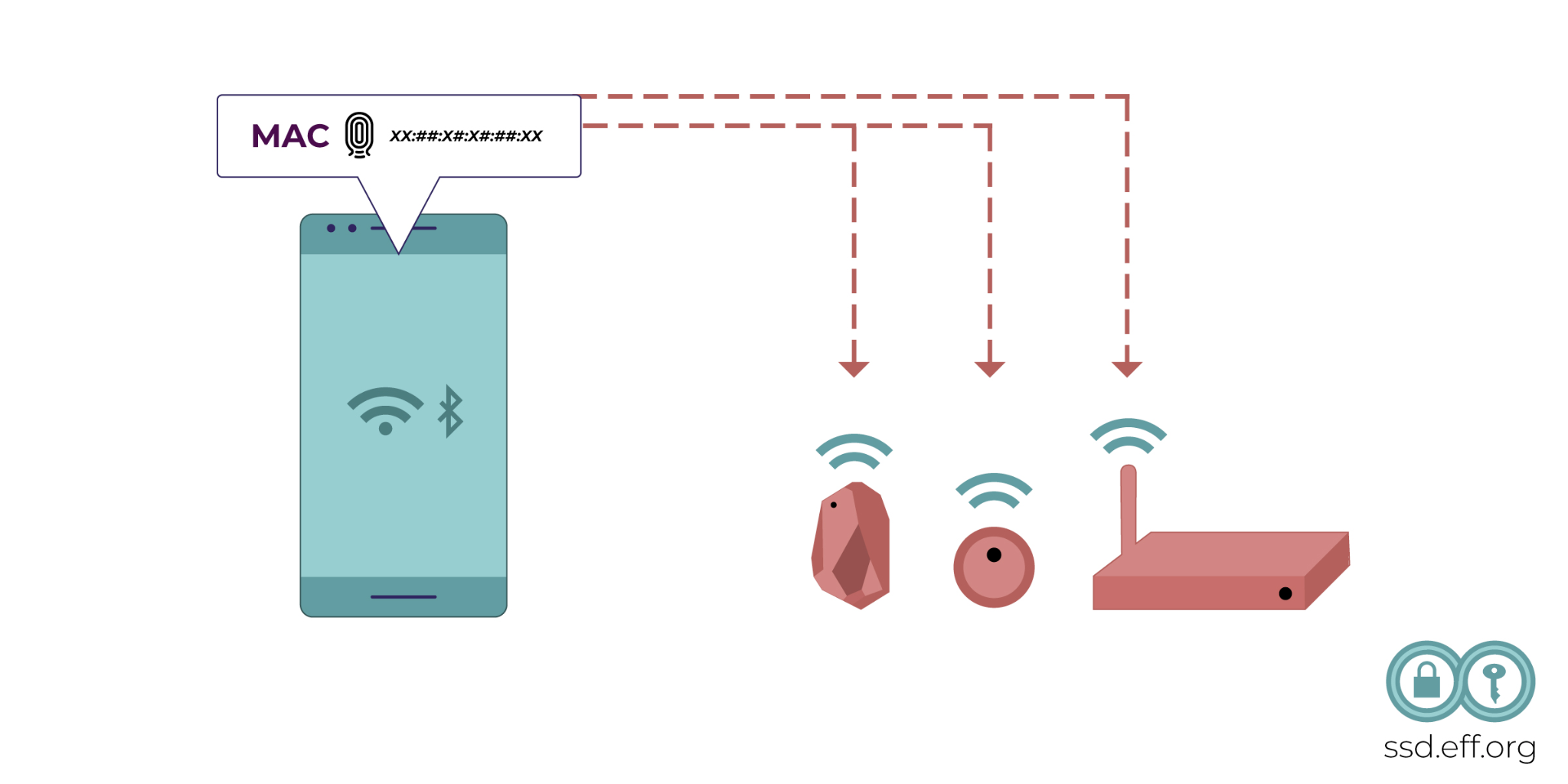

蓝牙与 Wi-Fi 信号均包含设备的唯一序列号(即 MAC 地址),对任何能够接收信号的人可见。当 Wi-Fi 开启时,一般智能手机会间歇性发送包含 MAC 地址的“探测请求”,使周边设备感知其存在。蓝牙设备亦有类似行为。传统上,此类标识符是零售店、咖啡馆等场所使用的被动追踪器(用于收集设备及人员的移动轨迹数据)的重要工具。美国边境也曾部署声称可捕获蓝牙 MAC 地址的蓝牙监控设备。

但在新版 iOS 与安卓系统中,探测请求所包含的 MAC 地址默认随机化,在很大程度上增加了追踪难度。由于 MAC 随机化依赖软件实现,因此并非绝对可靠,默认 MAC 地址仍存在泄露风险。此外,部分安卓设备可能未正确实施 MAC 随机化(PDF 下载)。

尽管现代设备通常在探测请求中使用随机地址,但在实际连接网络时(如配对无线耳机),多数设备仍会共享固定的 MAC 地址。这意味着只要有足够的时间,网络运营商就能够识别特定设备,并判断其用户是否曾经连接过该网络。此类识别甚至无需用户输入姓名、邮箱或登录任何服务。

应对措施:新版移动操作系统已启用 Wi-Fi 随机 MAC 地址功能。但此问题相当复杂,因为许多系统确有获取固定 MAC 地址的合理需求。例如,在接入酒店网络时,该网络需通过 MAC 地址跟踪设备授权状态;若设备 MAC 地址发生变化,该网络会将视其为新设备。iOS 18 及以上版本约每两周轮换设备的 MAC 地址。安卓系统的类似功能称为“随机化 MAC 地址”。若担忧此类监控,可临时关闭手机 Wi-Fi 或蓝牙功能。

应用及网页浏览导致的位置信息泄露

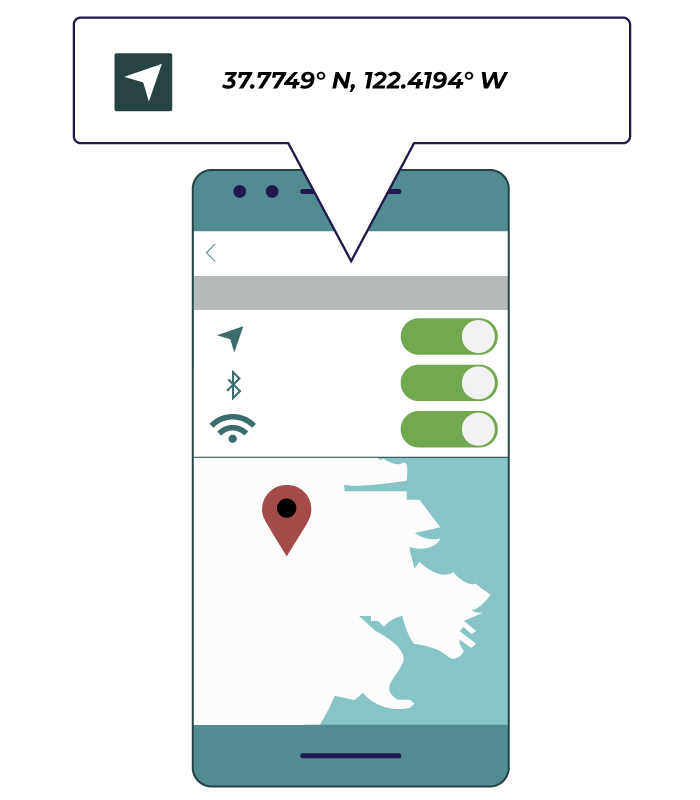

现代智能手机通常通过 GPS 或其他定位服务提供商提供的数据(通常基于设备可见的一系列基站或 Wi-Fi 网络来推测设备的位置)来确定自身的位置。Apple 与 Google 将此功能统称为“定位服务”。应用可向设备请求位置信息,用于提供基于位置的功能(如在地图中显示当前的位置)。

![]()

部分应用会将位置数据通过网络传输给服务提供商。这可能导致应用本身及服务提供商合作的第三方对用户进行追踪。应用开发人员可能无意追踪用户,但仍可能具备此类能力,并因政府要求或数据泄露事件而暴露用户的位置信息。

在这些情况下,位置追踪不仅涉及实时定位(如电影追逐场景中,特工在街头追踪目标),还可揭示历史活动、推测用户信仰、事件参与及人际关系。例如:利用位置跟踪功能来分析用户在某段时间接触的对象,从而推断恋爱关系;识别特定会议或抗议活动的参与者;或尝试锁定记者的匿名消息源。

据我们所知,执法机构曾屡次在无搜查令的情况下购买此类应用中收集的位置数据,其中涵盖历史与实时位置数据。

应对措施:尽可能限制应用获取位置权限,或在允许获取时仅提供“粗略”或“大致”的位置。安卓与 iPhone 均允许用户选择是否授予应用对位置的访问权限,以及可以访问的数据范围(在允许访问的情况下)。应审慎评估应用的运作是否依赖位置信息。例如,导航类应用需在使用时获取精确的位置,但天气应用是否需精确定位(手动输入邮编是否足够)?游戏应用是否需任何位置权限?存疑时应立即撤销权限(后续可随时调整)。

iPhone 用户可按此指南查看已获取位置访问权限的应用;安卓用户请按此说明操作。

行为数据收集与移动广告标识符

除部分应用与网站收集的位置数据外,许多应用会共享基础交互信息(如应用安装、打开、使用及其他活动)。此类信息常通过实时竞价 (RTB) 与广告生态系统中的数十家第三方公司共享。尽管单个数据点看似普通,但聚合后的行为数据仍可透露许多信息。

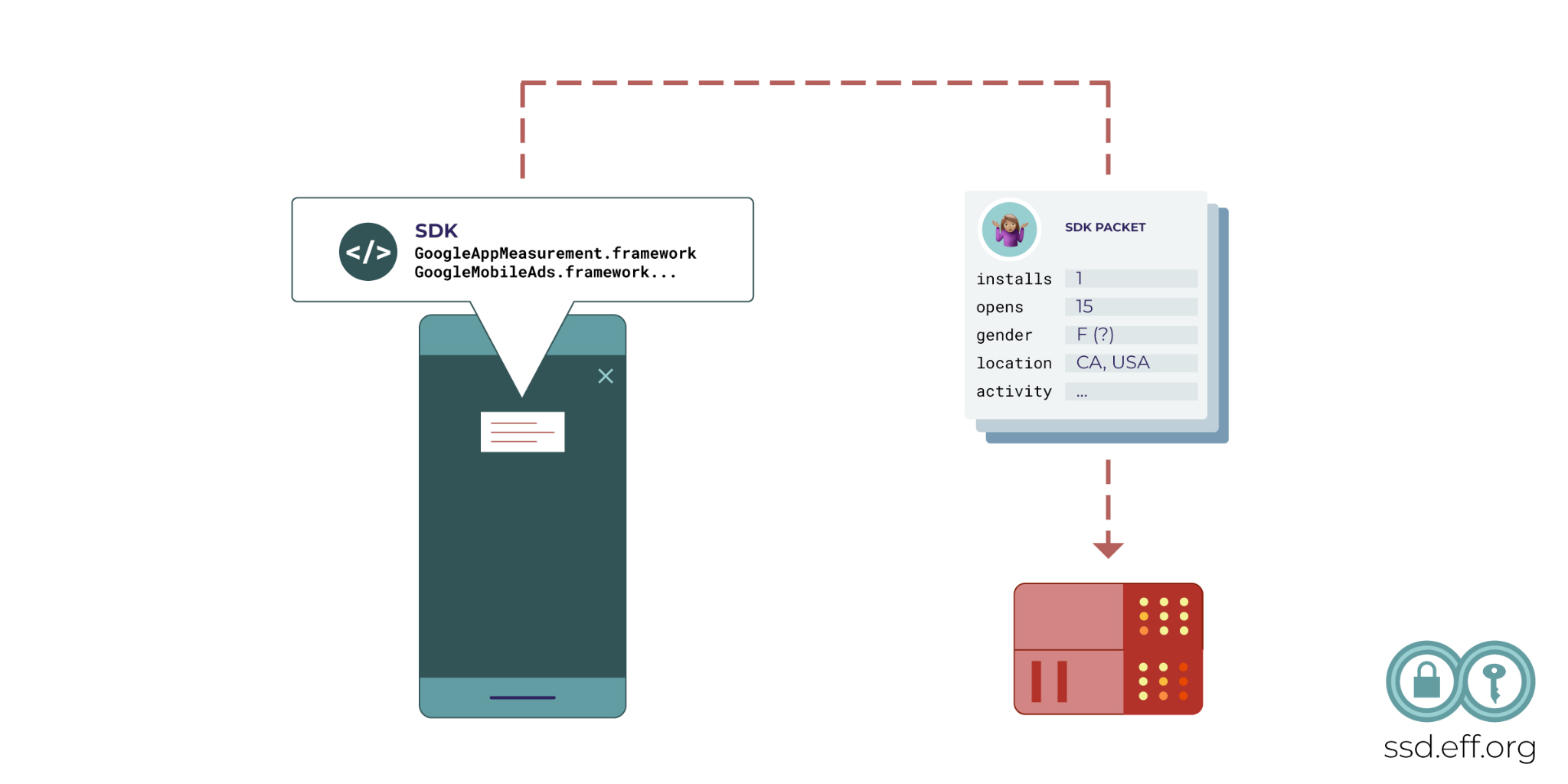

广告技术公司说服应用开发者在软件开发工具包 (SDK) 文件中安装代码片段,以便在其应用中投放广告。这些代码片段收集用户与应用的交互数据后,与第三方追踪公司共享。追踪公司可能进一步将信息提供给数十家广告主、广告服务提供商及数据中介。整个过程仅需毫秒级时间。

![]()

此类数据价值依托于移动广告标识符 (MAID)——标识单一设备的唯一随机数。RTB 中共享的每条信息通常都关联一个 MAID。广告主与数据中介可通过 MAID 整合来自不同应用的数据,从而构建由 MAID 识别的各用户行为画像。MAID 本身不包含用户的真实身份信息,但数据中介或广告主常能轻易将其与真实身份相关联。他们有多种方式可以做到这一点,例如,通过应用内收集的姓名或邮箱地址。

MAID 内置于安卓和 iOS 设备,以及游戏主机、平板电脑、电视机顶盒等多种设备中。在安卓系统中,所有应用及其中安装的所有第三方组件均默认可访问 MAID;最新版 iOS 要求应用在收集和使用 MAID 前申请权限。安卓用户可删除广告标识符(但需深入设置之中)。

移动应用收集的行为数据主要由广告公司和数据中介用于商业或政治广告的定向投放,但经证实,政府机构也会利用私营企业的监控结果。

应对措施:iOS 与安卓均提供禁止应用访问广告 ID 或完全关闭该功能的选项。安卓用户请按 Google 指南操作;iPhone 用户请禁止应用的追踪请求。