Mobile Phones: Location Tracking

Last Reviewed: November 05, 2024

Location Tracking

The deepest privacy threat from mobile phones—yet one that is often completely invisible—is the way that they announce your whereabouts through the signals they broadcast. There are at least four ways that an individual phone's location can be tracked by others:

- Mobile Signal Tracking from Towers

- Mobile Signal Tracking from Cell Site Simulators

- Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Tracking

- Location Information Leaks from Apps and Web Browsing

Mobile Signal Tracking — Towers

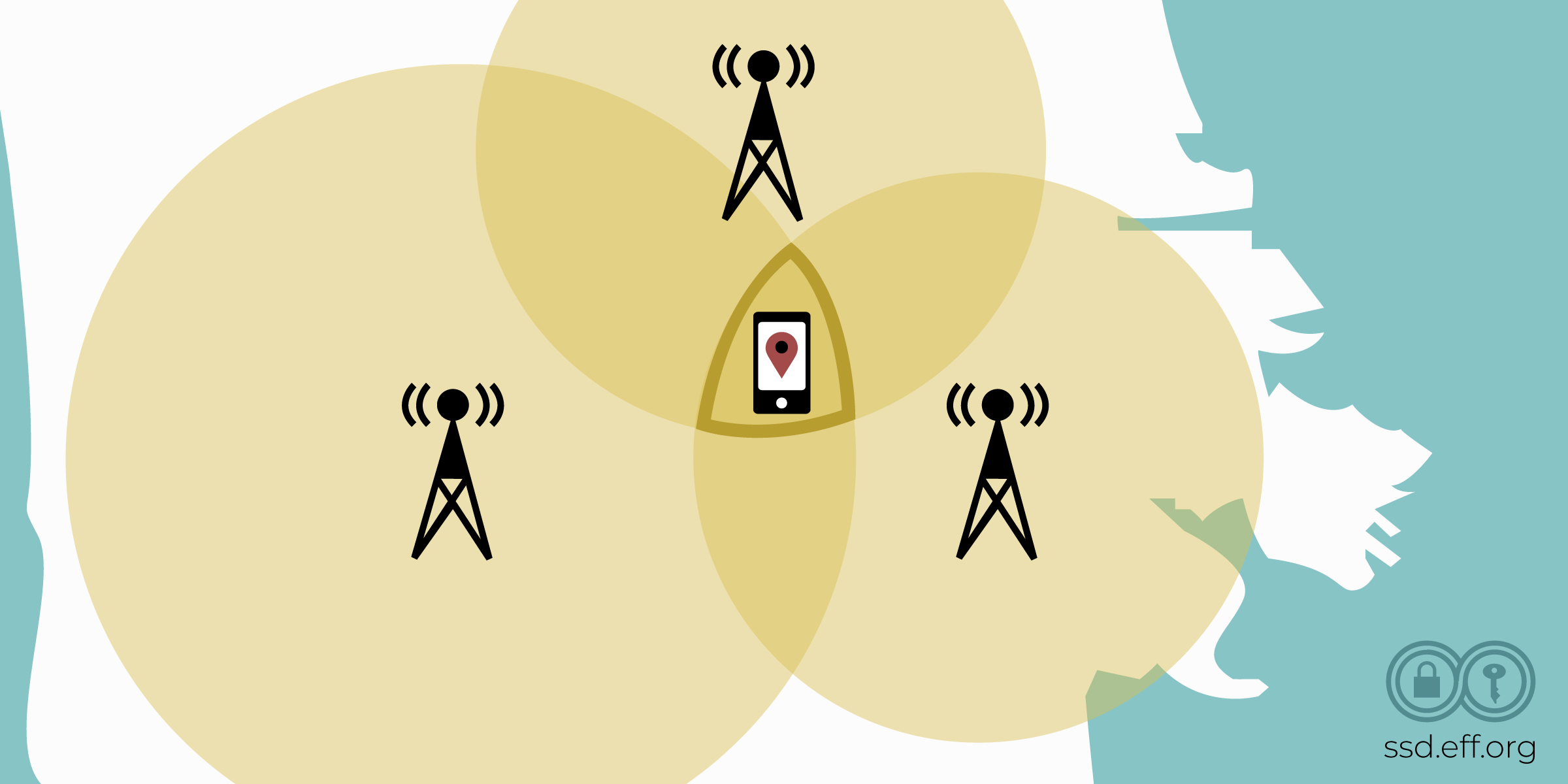

In all modern mobile networks, the cellular provider can calculate where a particular subscriber's phone is located whenever the phone is powered on and registered with the network. The ability to do this results from the way the mobile network is built with cellular towers, and is commonly called “triangulation.” If you’ve ever watched a modern day crime thriller, you’ve probably heard triangulation mentioned.

One way the mobile phone company uses triangulation is to observe the signal strength that different towers receive from a particular subscriber's mobile phone, and then calculate where that phone must be located. This is done with “Angle of Arrival” measurements.

The accuracy of these measurements to figure out a subscriber's location varies depending on many factors, including the technology the provider uses and how many cell towers they have in an area. Usually, with at least three cell towers, the provider can get down to 3/4 of a mile or 1km. For modern cell phones and networks trilateration is also used where a feature called “locationInfo-r10” is supported. This feature returns a report that contains the phone’s exact GPS coordinates, which is far more accurate than triangulation.

There is no way to hide from this kind of tracking as long as your mobile phone is powered on, with a registered SIM card , and transmitting signals to an operator's network.

Although normally only the mobile operator itself can perform this kind of tracking, a government could force the operator to turn over location data about a user (in real-time or as a matter of historical record). In 2010, a German privacy advocate named Malte Spitz used privacy laws to get his mobile operator to turn over the records that it had about his location. He also published them as an educational resource so that other people could understand how mobile operators monitor its customers this way. The possibility of government access to this sort of data is not theoretical: it is widely used by law enforcement agencies, including in the United States. In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled in Carpenter vs. United States that under the Fourth Amendment, police must get a warrant before obtaining this type of historical location data derived from cell carriers—known as “cell site location information,” or CSLI. Historical CSLI, the court wrote, creates a “detailed chronicle of a person’s physical presence compiled every day, every moment over years.”

A related kind of government request is called a “tower dump.’ Here, a government asks a mobile operator for a list of all the mobile devices that were present in a certain area at a certain time. This could be used to investigate a crime, or to find out who was present at a particular protest. EFF has asked courts to find tower dumps unconstitutional because they are overbroad and lack probable cause under the Fourth Amendment.

Carriers also exchange data with one another about a device location. This data is less precise than tracking data that aggregates multiple towers' observations, but it can still be used as the basis for services that track an individual device—including commercial services that query these records to find where an individual phone is currently connecting to the mobile network. This tracking does not involve forcing carriers to turn over user data; instead, this technique uses location data available on a commercial basis.

What you can do about it: Since this is handled by your cellular provider, there’s not much you can do to prevent this from happening beyond not carrying your cell phone with you. If your carrier informs you that law enforcement has demanded your data through a court order or warrant, you can contact EFF's legal assistance intake to see if we can help.

Mobile Signal Tracking — Cell Site Simulator

A government or a technically sophisticated organization can also collect location data directly, such as with a cell site simulator, also sometimes called an IMSI Catcher or Stingray. These are portable, fake cell phone towers that pretend to be a real one, in order to “catch” particular users' mobile phones, and detect their physical presence, and spy on their communications. IMSI refers to the International Mobile Subscriber Identity number that identifies a particular subscriber's SIM card, though an IMSI catcher may target a device using other properties of the device as well.

The IMSI catcher needs to be taken to a particular location in order to find or monitor devices at that location. IMSI traffic interception by law enforcement requires a warrant (and in many cases, an additional pen register order and other protections are required). However, a “rogue” CSS, (not set up by law enforcement) would be operating outside of those legal parameters.

What you can do: Currently there are some defenses against IMSI catchers. On Android, you can disable 2G connections, which many IMSI catchers use. You can disable 2G on an iPhone by enabling “Lockdown Mode,” though that also disables many other features. Additionally, it’s helpful to use encrypted messaging such as Signal, WhatsApp, or iMessage to ensure the content of your communications can’t be intercepted.

Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Tracking

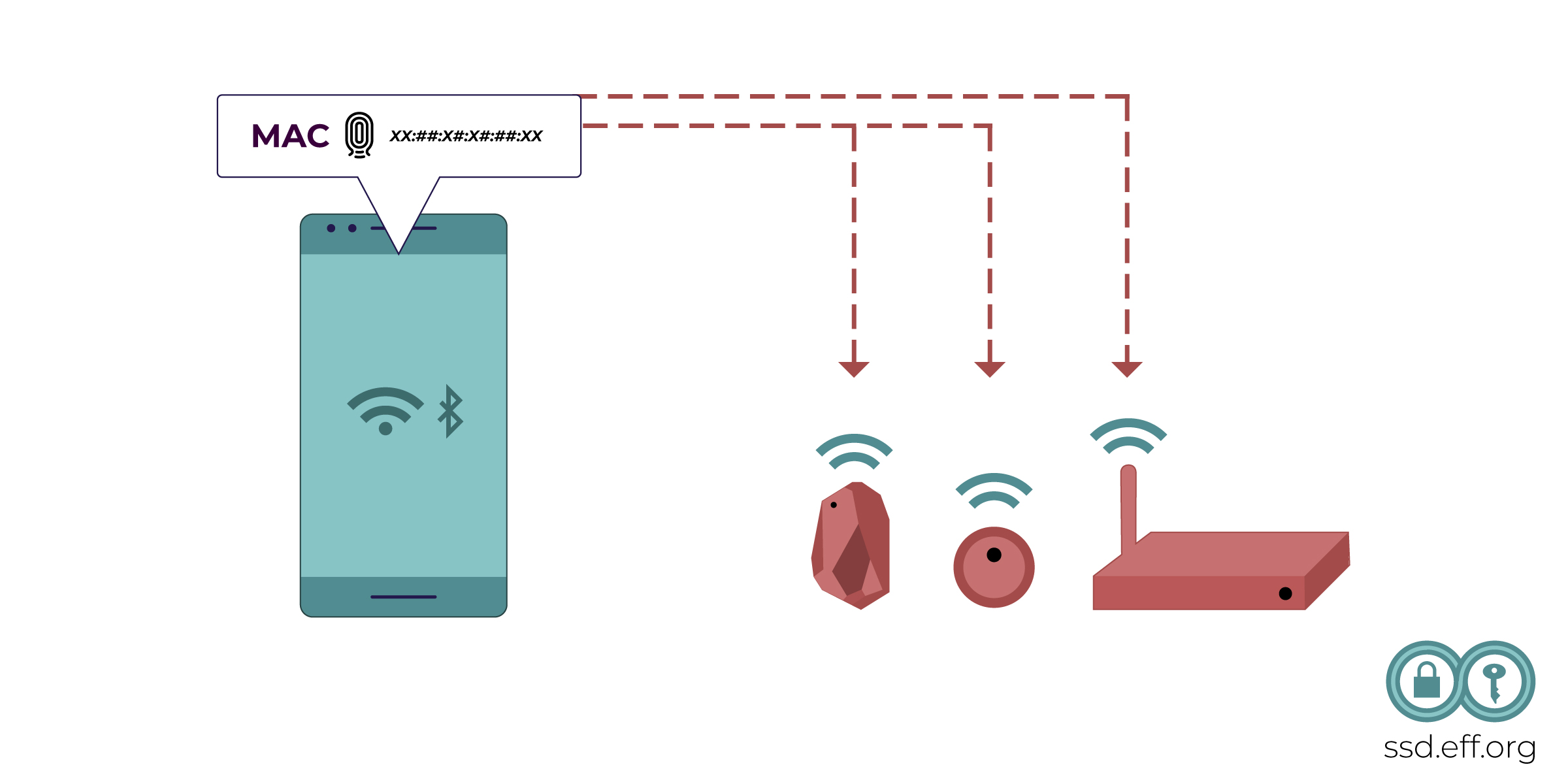

Modern smartphones have other radio transmitters in addition to the mobile network interface. They also have Wi-Fi and Bluetooth support. These signals are transmitted with less power than a mobile signal and can normally be received only within a short range (such as within the same room or the same building), although someone using a sophisticated antenna could detect these signals from unexpectedly long distances. For example, in 2007, an expert in Venezuela received a Wi-Fi signal at a distance of 382 km or 237 mi, under rural conditions with little radio interference. However, this scenario of such a wide range is unlikely.

Both Bluetooth and Wi-Fi signals include a unique serial number for the device, called a MAC address, which can be seen by anybody who can receive the signal. Whenever Wi-Fi is turned on, a typical smartphone will transmit occasional “probe requests” that include the MAC address and will let others nearby recognize that this device is present. Bluetooth devices do something similar. These identifiers have traditionally been valuable tools for passive trackers in retail stores and coffee shops to gather data about how devices, and people, move around the world. Bluetooth surveillance has also been used on the U.S. border, using devices that allegedly can capture Bluetooth MAC addresses.

However, on modern versions of iOS and Android, the MAC address included in probe requests is randomized by default, which makes this kind of tracking much more difficult. Since MAC randomization is software based, it is fallible and the default MAC address has the potential to be leaked. Moreover, some Android devices may not implement MAC randomization properly (PDF download).

Although modern phones usually randomize the addresses they share in probe requests, many phones still share a stable MAC address with networks that they actually join, like when you connect to a pair of wireless headphones. This means that network operators can recognize particular devices over time, and tell whether you are the same person who joined the network in the past. This can happen even if you don't type your name or e-mail address anywhere or sign in to any services.

What you can do: Modern mobile operating systems use randomized MAC addresses on Wi-Fi. But, this is a complex issue, as many systems have a legitimate need for a stable MAC address. For example, if you sign into a hotel network, it keeps track of your authorization via your MAC address. When you get a new MAC address, that network sees your device as a new device. iOS 18 and newer rotate the device’s MAC address about every two weeks. On Android, a similar feature is called “Randomized MAC address.” If you are in a situation where you are concerned about this sort of surveillance, you can turn Wi-Fi or Bluetooth off on your phone temporarily.

Location Information Leaks From Apps and Web Browsing

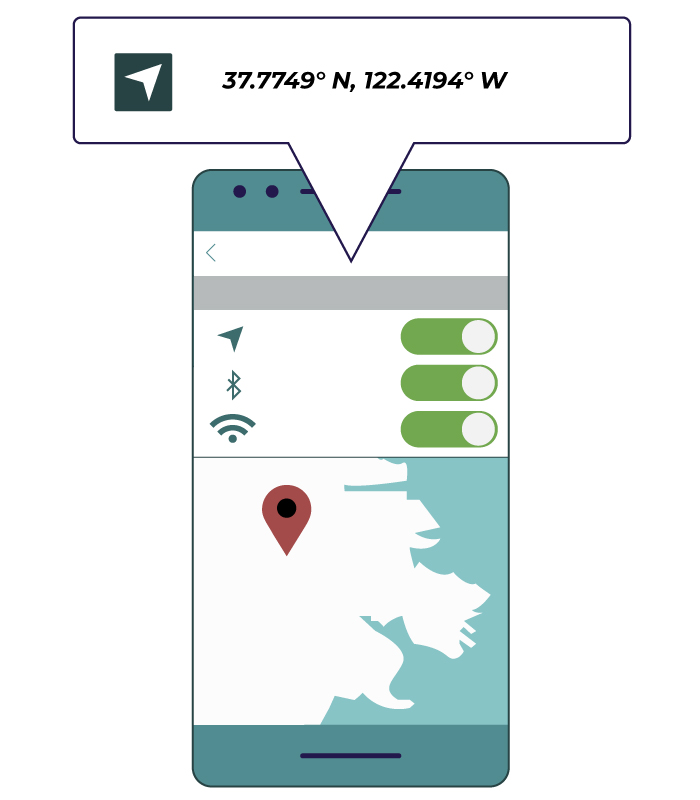

Modern smartphones provide ways for the phone to determine its own location, often using GPS, but also sometimes using other services provided by location companies (which usually ask the company to guess the phone's location based on a list of cell phone towers or Wi-Fi networks that the phone can see from where it is). This is packaged into a feature both Apple and Google call “Location Services.” Apps can ask the phone for this location information and use it to provide services that are based on location, such as maps that display your location on the map.

Some of these apps will then transmit your location over the network to a service provider. This could provide a way for the application and third parties the service provider shares with to track you. The app developers might not intend to track users, but they might still end up with the ability to do that, and they might end up revealing location information about their users to governments or a data breach .

In each case, location tracking is not only about finding where someone is right now, like in an exciting movie chase scene where agents are pursuing someone through the streets. It can reveal historical activities and also suggest information about their beliefs, participation in events, and personal relationships. For example, location tracking could be used to suggest when people are in a romantic relationship by following who they visit during certain times of day, to find out who attended a particular meeting, who was at a particular protest, or to try to identify a journalist's confidential source.

The location data collected in these apps has been purchased by law enforcement without a warrant, as we’ve seen numerous times. This can include both historical and real-time location data.

What you can do: Cut access to your location in as many of your apps as possible, or only provide apps with “course” or “approximate” location when you can. Both Android and iPhone allow you to choose whether an app can access your location, and how much data it can access if so. Think about whether an app needs your location to function. For example, a navigation app for driving directions will need your exact location when you’re using the app. But does your weather app need to know exactly where you are or would manually typing in your zip code suffice? Does that game you downloaded need your location at all? Revoke access any time you’re not sure. You can always change your mind.

On iPhone, follow these directions to review the apps you’ve given location access to. On Android, review the apps you’ve given location access to by following these instructions.

Behavioral Data Collection and Mobile Advertising Identifiers

In addition to the location data collected by some apps and websites, many apps share information about more basic interactions, such as app installs, opens, usage, and other activity. This information is often shared with dozens of third-party companies throughout the advertising ecosystem enabled by real-time bidding (RTB). Despite the mundane nature of the individual data points, in aggregate this behavioral data can still be very revealing.

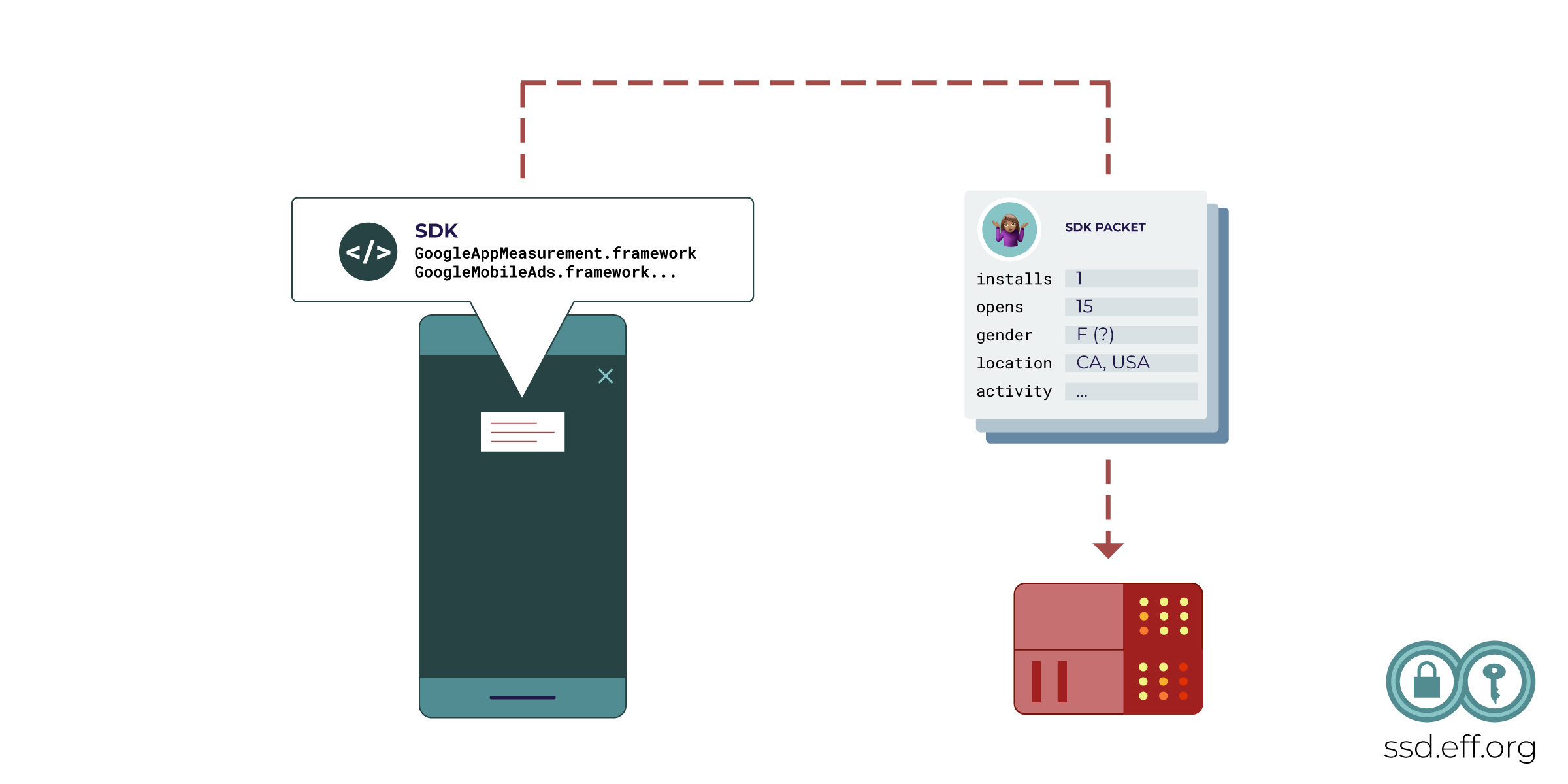

Advertising technology companies convince app developers to install pieces of code in software development kit (SDK) documentation in order to serve ads in their apps. These pieces of code collect data about how each user interacts with the app, then share that data with the third-party tracking company. The tracker may then re-share that information with dozens of other advertisers, advertising service providers, and data brokers. This whole process takes just milliseconds.

This data becomes meaningful thanks to the mobile advertising identifier (MAID), a unique random number that identifies a single device. Each packet of information shared during an RTB auction is usually associated with a MAID. Advertisers and data brokers can pool together data collected from many different apps using the MAID, and therefore build a profile of how each user identified by a MAID behaves. MAIDs do not themselves encode information about a user’s real identity, but it’s often trivial for data brokers or advertisers to associate a MAID with a real identity. They have several tactics for doing this, like collecting a name or email address within an app.

Mobile ad IDs are built into both Android and iOS, as well as a number of other devices like game consoles, tablets, and TV set top boxes. On Android, every app, and every third-party installed in those apps, has access to the MAID by default. In the latest versions of iOS, apps need to ask permission before collecting and using the phone’s mobile ad ID. On Android, you can remove the ad ID, but you’ll have to dig into the settings.

Behavioral data collected from mobile apps is used primarily by advertising companies and data brokers, usually to do behavioral targeting for commercial or political ads. But governments have been known to piggyback on the surveillance done by private companies.

What you can do: Both iOS and Android offer ways to disable app’s access to the ad ID, or just disable the feature entirely. On Android, follow Google’s directions here. On iPhone, don’t allow apps to ask to track you.